ESG Is Not Enough - Part III: Piercing Through Buzzwords

Author: Massiel Valladares | Editors: Anas Attal, Isabelle Pierotti, and Saeyeon Kwon; Managing Editor: Jaishree Singh

Today’s sustainable finance world relies on vague and ill-defined acronyms. If financial markets are to be a force for good, we must embrace a more intentional approach.

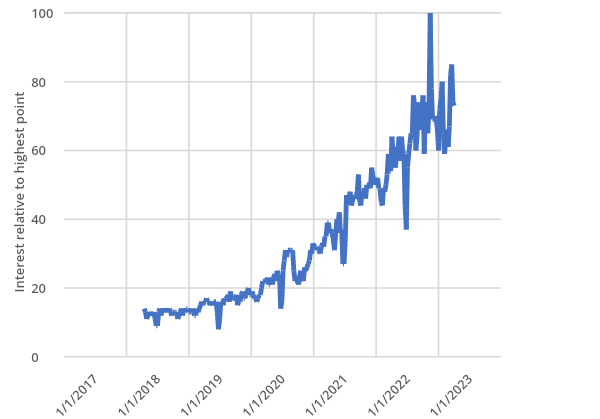

Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) discourse and activity are on the rise. This is no news to the investing world, which has witnessed ESG-related assets under management (AUM) skyrocket globally from $2.2. trillion in 2015 to $18.4 trillion in 2021, with PwC forecasting a 12.9% compound annual growth rate (CAGR) in the next 5 years. This staggering growth has not gone unnoticed in mainstream social and political spheres. ESG interest from the general public, as defined by Google searches, achieved its peak in May of this year, as seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Google search for “ESG” — Worldwide, Oct 2018 — Oct 2022

But what exactly is ESG? Acronyms like ESG, CSR, and DE&I dominate corporate rhetoric, and for many, this language is obfuscating. When it comes to ESG and its related terms like impact and green investing, ill-defined and ever-changing terminology might hinder the public’s willingness to embrace the value brought forth by the concept of sustainable finance as a whole. Current anti-ESG political rhetoric, which relies on fear-mongering, straw man, and slippery slope fallacies, threatens to curb crucial momentum in the transition to more sustainable and inclusive capital markets. While acknowledging the important limitations of ESG, clarifying its origin and definition are essential to disrupting this discourse.

Contextualizing ESG: A Brief History of Responsible Investments

Ethical and social considerations have long been investment criteria. The 1960s-1980s popularized the concept of socially responsible investing in the United States as protests against the Vietnam War and South African Apartheid ramped up and investors demanded the exclusion of certain stocks and industries. In parallel, the “social contract” concept — whose modern application was developed by political philosopher Thomas Hobbes — propagated in the 1970s in the context of business and society, further cementing the link between these two and laying the groundwork for the inclusion of corporate social responsibility (CSR) in firms’ business models. Though CSR was a step forward in moving beyond the shareholder-centric, profit-only corporation, its largely self-regulated nature lacked measurability and comparability between firms.

The early 2000s observed the formal creation and integration of ESG in investment analysis, with the 2005 UN Global Compact’s Who Cares Wins initiative and the release of the 2006 United Nations Principles for Responsible Investment (UN PRI). The formalization of ESG was a milestone in embedding measurability and accountability into businesses’ environmental, social, and governance performance, but its widespread adoption by the capital markets was not without delay. The 2008 Great Recession revealed the dire, global, and interconnected consequences of the lack of comprehensive social responsibility in investing. Since then, impact-driven investment has seen tremendous exponential growth.

Photo by Mathias Reding on Unsplash

Defining Impact-Driven Investing

Today, Capital Groups’ ESG Global Study for 2022, drawing from a sample of +1,000 institutional and wholesale investors from 19 countries, reveals that almost 9 out of every 10 institutions have adopted ESG to varying degrees: central to the firm’s investment approach (28%), applied to approach (32%), and considered in investing decisions (24%). These differentiations are important, as they reveal the lack of uniformity along ESG integration, defined as a deliberate inclusion of material ESG factors into investment decisions.

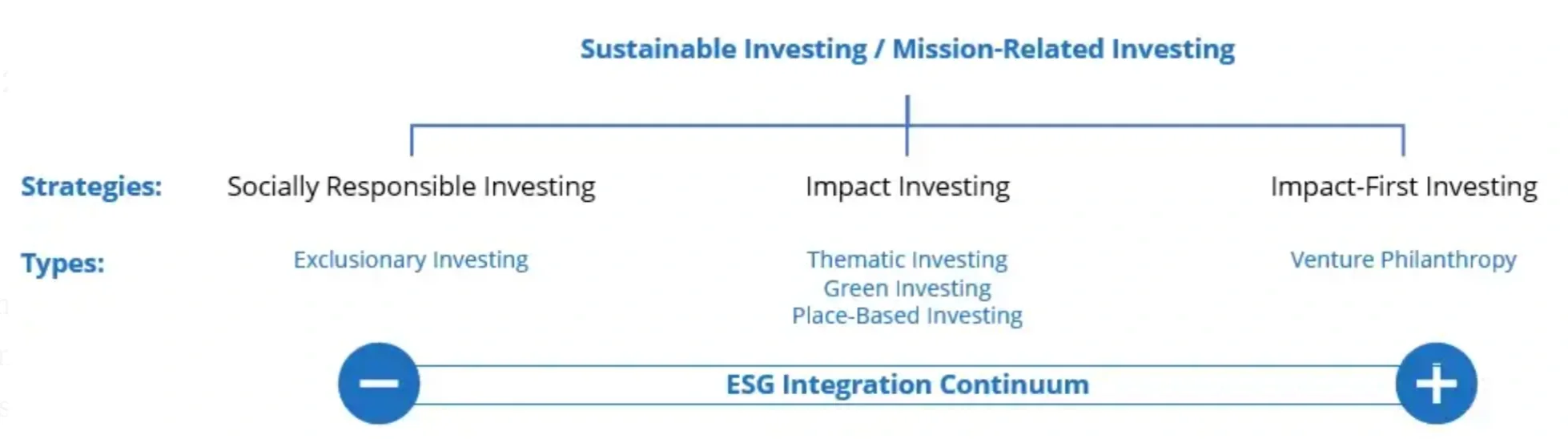

Adapted from Nasdaq (2021) and Deloitte (2021).

A common misconception is that ESG is an asset class or a singular investment strategy. In actuality, ESG is a framework that can inform a range of investment strategies along the ESG criteria integration continuum. With the pursuit of long-term value creation, these strategies fall under the umbrella terms “sustainable investing” and “mission-related investing,” summarized in Figure 2.

Socially responsible investing (SRI) may consider ESG criteria but is mostly based on an exclusionary investment strategy through screening and divestment. An SRI product, like SRI equity mutual funds, which were popular in the 1990s and early 2000s, might use negative screens to exclude alcohol and tobacco stocks.

Impact investing is more proactive in its integration of ESG criteria and risk management, including non-financial impact in addition to profitability. Thematic impact investing is a type of impact investing that focuses on specific ESG-related themes, like climate change or financial inclusion. Place-based investing, which seeks to deploy capital in specific locations to serve marginalized communities while generating financial returns, is yet another type. Different instruments can be used to achieve these types of investments, like green bonds and green loans.

Impact-first investing considers ESG criteria as a priority and may hold below-market returns or no returns at all, like venture philanthropy and traditional philanthropy.

From Acronyms to Action: Connecting Sustainable Finance with Sustainable Development

As described in 17AM’s 2020 The ESG-SDG Capital Continuum report, ESG is a framework. Today, the risk-rating and standard-setting players in the ESG space assess “the degree to which environmental, social, and governance issues impact a company’s ability to create value for shareholders,” which means that ESG is a complementary risk assessment to financial and security analyses.

Photo by Robert Bye on Unsplash

While significantly more impactful than the business-as-usual traditional investment strategies, ESG ratings and scores — riddled with their standardization, methodological, and enforcement challenges — are not enough to mobilize the capital markets at the scale needed to respond to today’s most pressing issues.

The current ESG-dominated financial market can contribute directly and indirectly to sustainable development while maintaining financial returns for investors. However, competing terminology within the sustainable finance space might indicate the lack of clarity around its potential to be an intentional force for good. As the rise of greenwashing demonstrates, the uncertainty, both for the general public and investors themselves, around what exactly constitutes ESG reduces the potential impact of public relations maneuvers while justifiably increasing public skepticism. If we can’t even unify the terminology around this space, how can we ensure continued critical support for sustainable finance?

Closing Thoughts

At 17AM, we believe the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) can provide a supplemental strategic framework that can embed intentionality into the capital markets. Our 2019 Institutional Intentionality Report delineates the definition and importance of the Sustainable Development Goals: “The SDGs are an articulation of the world’s most pressing development challenges, framed by the United Nations as those facing people, planet, and prosperity.” The final piece in our ESG is Not Enough mini-series elucidates the impact potential of the SDG framework in reshaping the capital market’s commitment to a sustainable, inclusive future.