ESG Is Not Enough - Part II: What’s Wrong with Rating Agencies?

Author: Saeyeon Kwon | Editors: Anas Attal, Massiel Valladares, and Isabelle Pierotti | Managing Editor: Jaishree Singh

ESG ratings are a common tool for measuring a company’s exposure to non-traditional financial risks, namely, environmental, social, and governance risks. Stakeholders, including asset owners and institutional investors, increasingly demand more specific and transparent ESG information, and Government regulators are requesting ever stricter disclosures, to meet the Paris Agreement’s 1.5-degree target. Based on a company’s ESG data disclosure, ESG rating agencies assess ESG factors to come up with a rating that investors often rank above a company’s disclosures in importance.

However, the variety of ESG rating methodologies elicits questions regarding their reliability and credibility.

Photo by Nick Chong on Unsplash

Demand for ESG information has increased dramatically in recent years with the expansion of ESG-based investment. According to a report by PwC, in 2022, global ESG investment assets surpassed $18.4 trillion in 2021, and are on track to reach $33.9 trillion by 2026. This accounts for more than one-fifth of the projected $157.2 trillion in total assets under management globally. It is, therefore, important that investors are fully aware of the issues with ESG ratings, and strategies commonly employed to mitigate uncertainties associated with them.

Inconsistency Between Rating Agencies

A recent study from MIT reported that correlations among ESG ratings ranged from 0.38 to 0.71. This lack of correlation is a fundamental issue for investors that stems not just from rating methodology, but disagreements regarding the underlying data. For example, data such as carbon emissions and energy consumption can be rigorously quantified, but social and governance data and their associated scores can differ based on the particular criterion used. This means ratings of the same company can vary significantly, and they may reflect inaccuracies in assessment metrics. Furthermore, it is often difficult to determine the reasons for this variance as most agencies do not fully reveal their methodology, creating transparency and credibility concerns.

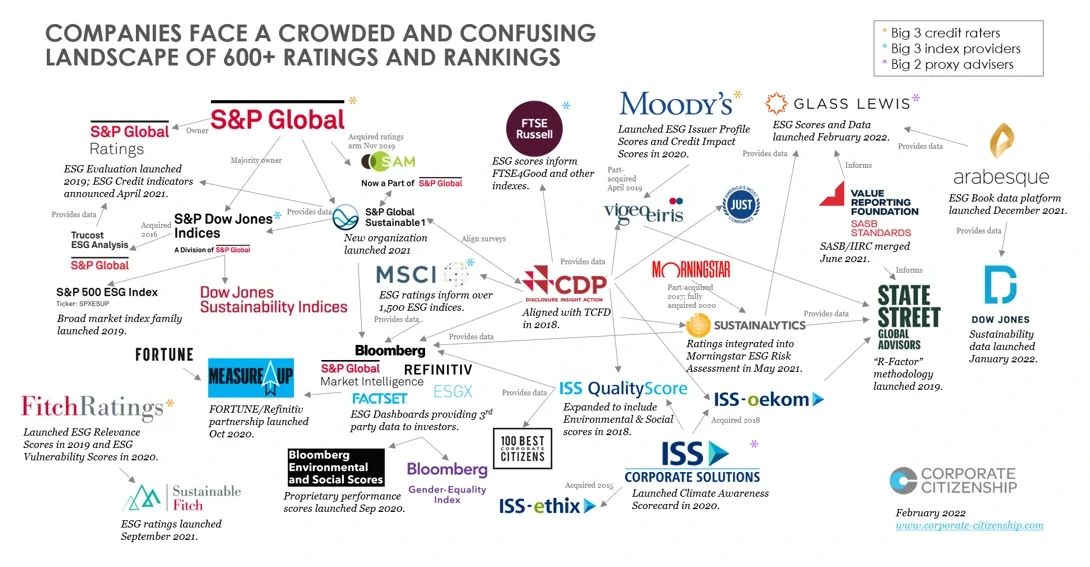

There are currently over 600 rating agencies, including MSCI, S&P Global, Sustainalytics, ISS ESG, Bloomberg, Moody’s, and Dow Jones Sustainability Indices, with ISS ESG, MSCI, and Sustainalytics being the most popular. The core purpose of major rating agencies is to identify ESG risks that might pose risks to the company’s business model, operations, and economic value.

ISS ESG industry-specific indicators select 5 key issues in each industry, which account for 50% of the overall weight in a rating on an A+ to D- scale. MSCI uses a similar approach, but selects 35 key issues for each industry, and weights them based on a materiality mapping framework on a AAA to CCC scale. In contrast, Sustainalytics uses a material ESG issue (MEI) approach to rate companies from negligible to severe, which identifies if the presence or absence of an MEI in financial reporting is likely to influence the decisions made by a reasonable investor.

To minimize the discrepancies between ESG ratings, they should be used as a starting point, and combined with other KPIs, to understand a company’s overall sustainability as a business. This is a common approach in the finance industry, with SquareWell reporting that 38 out of 50 of the world’s largest asset managers use two or more ESG rating providers. Large firms often even combine this with their internal systems to assess a company’s ESG performance. However, inconsistencies aside, for a true reflection of a company’s environmental, social, and governance performance, it is necessary to look beyond these ratings.

ESG Ratings Don’t Measure True ESG Quality

A common misconception regarding ESG ratings is that high-rated corporations will perform significantly better in terms of corporate social responsibility, have a lower harmful environmental impact, and treat their employees exceptionally well. However, it is important to remember, as recently pointed out by the corporate governance research initiative at Stanford Graduate School of Business, current ESG ratings are not designed to measure the real ESG impact of a company, but to quantify investment risk.

As an example, the Coca-Cola Company (NYSE: KO), consistently scores highly in ESG ratings, achieving an AAA rating from MSCI in 2022 and a score of 22.8 Medium risk from Sustainalytics. Recent controversy, however, highlights weaknesses in these ratings. According to Break Free From Plastics, Coca-Cola is the world’s worst corporate plastic polluter for the fourth year in a row, despite claims that it would get every bottle back by 2030 and uses bottles made with 100% recycled plastic in 18 markets.

Photo by Tanvi Sharma on Unsplash

Nestle (NSRGY) also received a score of AA from MSCI in 2021. However, in 2020, along with other major chocolate companies, they were accused of assisting and abetting the illegal enslavement of thousands of children on cocoa farms in Ivory Coast (or Côte d’Ivoire) in West Africa.

Questionable ESG ratings do not stop at the food industry. Major banks, such as JP Morgan & Chase (JPM) and Bank of America, (BAC) are among the top five banks financing fossil fuels and have received scores of AA and A from MSCI ESG Research.

The preceding example illustrates a fundamental flaw in the use of ESG for sustainable investing. Since ESG ratings might not accurately reflect the commitment of a company to sustainability, there are often opportunities to abuse the measure to make the company seem more sustainability-conscious than it is.

Why Greenwashing Is So Harmful

Deloitte describes greenwashing as “a situation in which a firm makes misleading or exaggerated claims about the environmental benefits of its products or services”. Analogously, ESG washing exploits flaws in ESG rating systems to make misleading claims about a company’s sustainability. Since the ESG rating score relies heavily on a company’s voluntary sustainability reporting, it invites opportunism in the false or misleading characterization of a company’s ESG efforts. Indeed, according to a survey conducted by Capital Group, almost 5 in 10 global investors (48%) think greenwashing is prevalent within the asset management industry.

Moreover, researchers have identified an effect caused by human analysts conducting ratings: due to rater bias, performance in one category can affect the perception of performance in other categories. The authors further noted that it is possible if ESG rating firms divide analyst labor by firm, not by category, which implies that if an analyst’s overview of a company is positive, it may extend into the assessments of other categories. Thus, when evaluating companies, investors should be aware of these shortcomings and maintain a healthy skepticism when interpreting ESG ratings.

Closing Thoughts

ESG ratings have become the de facto metric in measuring a company’s sustainability profile and not simply its environmental, social, and governance risk. This has led to issues surrounding the use of ESG ratings in guiding sustainable investing. Besides inconsistencies in rating methodology and interpretation, voluntary reporting makes it too easy for companies to greenwash their environmental and social impact. However, this is at least evidence of mounting pressure from investors for companies to demonstrate a commitment to sustainable practices.

At 17AM, we apply a dual approach through ESG and the UN SDGs. We utilize ESG to assess the company's financial risks and SDG to assess the actual impact on our world.

As discussed above, although companies might achieve high ESG scores from rating agencies, their SDG achievement should be scrutinized. In this way, we can mitigate possible greenwashing, to get a more holistic view of a company’s sustainability profile. Using this approach, our firm can use investing as a tool to address contemporary social issues and bring a real positive impact that benefits both our society and investors.