Demystifying Impact Part 1: Every Investment Stage Should Be Data-Driven

Author: Massiel Valladares; Editors: Anas Attal, Isabelle Pierotti, Saeyeon Kwon; Managing Editor: Jaishree Singh

“In the absence of evidence of social return, ‘impact investing’ is… little more than traditional investing with a fancy public relations window dressing”

– Jane Reisman Ph.D., Veronica Olazabal, & Shawna Hoffman at The Rockefeller Foundation

The defining characteristic of impact investing is “impact.” Without it, the term’s sole difference with traditional “returns-only” investing is its public relations disguise. When discussing “impact,” practitioners in the field typically mean the general positive non-financial change created by companies who receive investments. Impact investing, then, can be defined as an investment strategy that incorporates both financial and non-financial criteria; the degree to which one is prioritized over the other can vary, with ESG-based investing prioritizing both and venture philanthropy investing focusing on the latter.

Social impact, more specifically, is a positive change that addresses and aims to solve social injustices and issues. As opposed to the easily quantifiable financial impact, social impact is notoriously hard to measure - social challenges are often interconnected, various actors seek to address issues at the same time, and data by itself cannot paint a complete picture of the state of individuals, communities, and society at large. Evaluation professionals in development and philanthropy fields have spent decades working on methods to “prove'' impact to donors. In the philanthropy space alone, the Rockefeller Foundation estimated that there are currently over 30 organizations developing methodologies to assess impact. For a relatively nascent field like impact investing, two fundamental questions emerge:

How can impact investors know their portfolios allocate capital to genuinely impactful firms?

For more targeted approaches, how can stakeholders know their investments are generating impact?

Photo - WEF Davos

PC: Evangeline Shaw on Unsplash

The increasing importance of impact measurement and management (IMM)

Impact measurement and management (IMM), if applied correctly and robustly, might help answer the two questions above. Impact measurement aims to evaluate the effects of investments, both positive and negative. Impact management seeks to continuously leverage data to track progress in various social impact indicators (e.g. yearly CO2 reduction, monthly jobs creation) to manage impact portfolios. Together, these concepts represent a holistic and engaged approach to achieving three main objectives, as proposed by the Harvard Business School:

Directing the allocation of funds to high-impact opportunities and firms

Accurately and thoroughly assessing the impact of previous investments

Establishing accountability for impact performance

These objectives lie at the core of authentic impact investing. The Global Impact Investing Network’s (GIIN) 2018 Roadmap for the Future highlighted the need to “develop and share best practices for impact measurement, management, and reporting” to strengthen the identity of impact investing itself if the field is to guide a cohesive, scalable social movement in the finance world. Evidently, in a 2018 paper for the American Journal of Evaluation, Jane Reisman, Veronica Olazabal, and Shawna Hoffman emphasized the growing demand for data and evidence of social outcomes in impact investing. As this demand increases, so does the realization among investors and portfolio managers that current impact measurement methodologies fall short.

The demand for data-driven evidence of impact points to a sea change that must occur in the field: we must embrace a data-driven ethos that prioritizes long-lasting change over financial and output data. Currently, data transparency, availability, and quality seem to be some of the biggest challenges to overcome in advancing IMM. As per the GIIN’s 2020 report on the current state of IMM, transparency on impact performance was the category with the lowest perceived progress. Similarly, in a separate question, investors’ top self-reported challenges around IMM were the lack of quality data (92%), the inability to compare impact with market performance (84%), and difficulty aggregating and analyzing relevant data (73%). Firms' impact targets remain arbitrary without appropriate benchmarking due to data gaps. Arbitrary target-setting is akin to students evaluating themselves on their own exams: by self-determining their threshold for success, firms’ under or overperformance is solely a measure of how well the firm met criteria conveniently outlined in the first place.

Summarizing IMM along the investment process

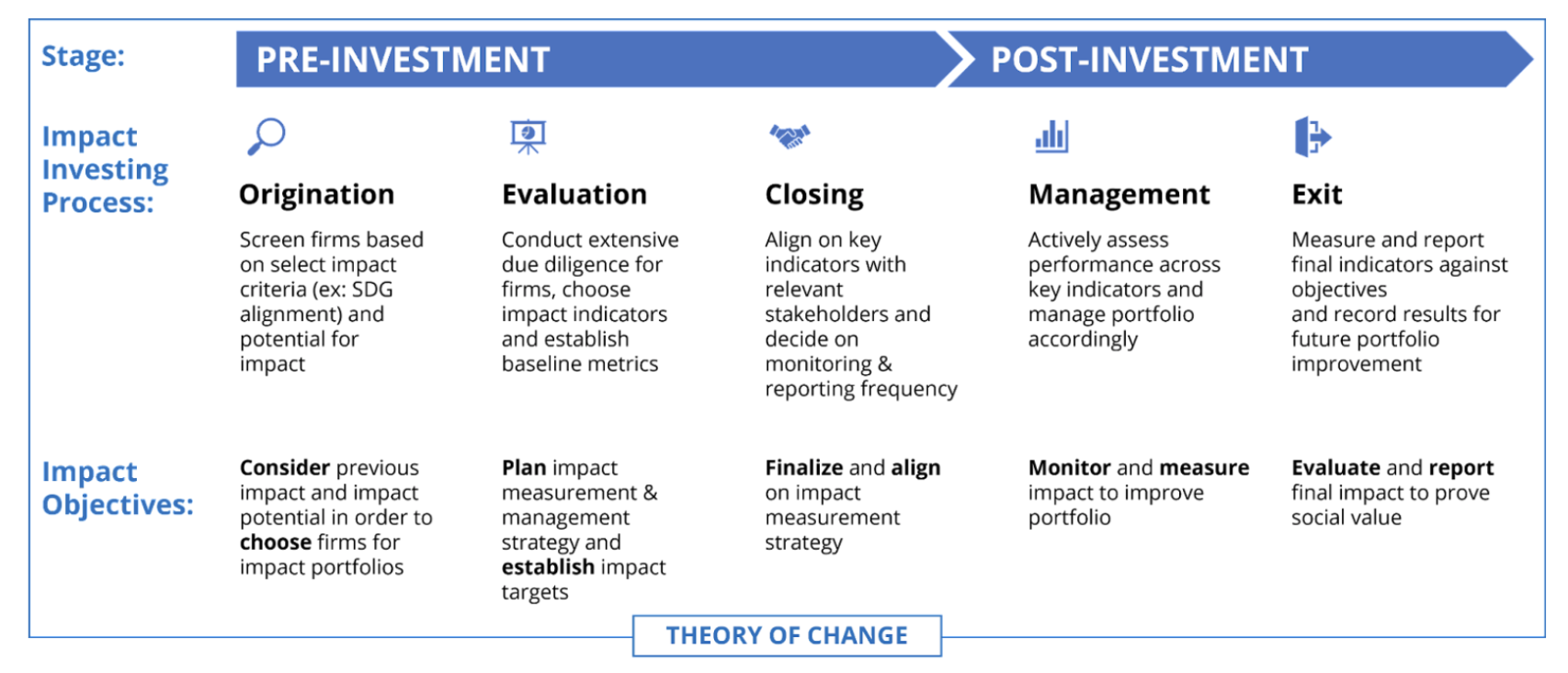

A robust IMM strategy tackles the meaning of “impact” at each stage of the investment process and considers the different roles and responsibilities of relevant stakeholders in each stage.

Without the history and widespread applicability of impact measurement in the philanthropic sector, IMM methodologies and rigor vary widely across different firms’ investment processes, as thoroughly detailed by So & Staskevicius in their 2015 report “Measuring the ‘Impact’ in Impact Investing.” For simplicity, we can classify the role of IMM into two main camps:

Pre-investment IMM refers to the screening and due diligence steps before investment, from origination to evaluation, in which companies’ existing impact and impact potential are assessed. This category can also include impact forecasts and planning.

Post-investment IMM refers to the measurement and management of impact resulting from that investment. At this stage, firms measure, monitor, and assess the effects of their investment across previously established key indicators.

Sources: 17AM’s Investment Process. Impact objectives adapted from Ivo So & Alina Staskevicius, “Measuring the ‘Impact’ in Impact Investing.” Harvard Business School, 2015.

A theory of change, also known as a logic model, lays out the basic framework and process for an organization’s intended social impact and usually includes the causal linkages among five components: inputs, activities, near-term outputs, longer-term outcomes, and overall impact. While this model can be used in conjunction with other IMM methodologies for specific investments and projects, the impact investing process itself should be embedded within a theory of change that articulates why and how impact investing can lead to social change. Thus, a science-based theory of change should be a prerequisite for pre-investment and post-investment IMM.

Introducing 17AM’s Demystifying Impact Series

This mini-series will aim to answer the two questions posed at the beginning: How can impact investors know their portfolios are allocating capital to genuinely impactful firms? And for more targeted approaches, how can stakeholders know their investments are generating impact? For the first question, we will critically examine common pre-investment methodologies like positive and negative screening. For the second question, we will summarize different approaches to post-investment impact measurement, examining both their strengths and shortcomings.

Our aim is threefold: We wish to 1) elucidate the current state of IMM in a digestible way and 2) apply a critical lens to this process, acknowledging its strengths and weaknesses 3) encourage both practitioners and investors to engage more intentionally and rigorously with IMM.

17AM’s research reveals that robust, ongoing, and transparent IMM is key for any impact-focused product throughout its investment cycle, from origination to exit. We’re prepared to help you integrate these best practices into your investment process.

Be sure to read Part 2 of our mini-series “Demystifying Impact” called “Good Day for Humans, Sad Day for Robots” and follow 17 Asset Management on Medium to receive timely updates.